Lectio Præcursoria

Picture 1. Collagerator

In 2000 I finished my master of arts final work Collagerator. It was a CD-ROM multimedia work which created collages, complete with a layered sound collage and the possibility to print the collages. The users selected images for three different layers from predefined image banks, pressed the return key and saw a collage of those images (Picture 1).

While Collagerator was exhibited, two things emerged, which I hadn’t given too much thought when making the work. The first is the issue of authorship that the users experienced while using the work. While the users played around with Collagerator they often expressed to me how they felt that they were doing the art, creating the collage. The second thing was the fluid user experience of the intearctive artwork. I frequently heard comments, that my work was — at least for most people — easy and fun to use, while others on display in Helsinki in the same exhibition appeared confusing to many: people didn’t know how to operate them, or if what they were doing was affecting the work at all.

About 10 years ago, I started to work with my doctoral dissertation and the interactive artwork related to it. After a while, these two issues surfaced again, guiding the research process and its related artistic part to a new track after initial fumbling with visual music. At that time there was not so much research work on interactive art published, at least in Finland. I realised that for interactive art, there is a different kind of thinking one needs: a certain amount of usability is needed in order to be able to create the sense of authorship for the user. In interactive art, the work becomes alive, or manifests itself through its usage. Unfortunately, not everyone working with interactive art seem to understand this.

“I'm the bloody artist, I made it that way, if the users don't understand it then it's their problem not mine!”

This quote from a famous media artist not to be named displays an attitude, in which only the artist knows how to interact with the work, ignoring or even mocking any others who try to understand how the interactive artwork functions. Meanwhile, his work stood in the exhibition silently as no-one figured out how to use it. I have experienced other kind of ignorance as well. While setting up my artistic part of this thesis, the interactive installation Climatable at the St. Etienne Biennale, another media artist exhibiting in the same room brought in his interactive installation (basically a sculptural contraption, where the user climed inside to encounter a computer screen and a mouse, which was to be moved around the screen). The artist plugged in the power and left. After 15 minutes I noticed the screensaver of the computer was turned on, asking for a password. Simultaneously, I was setting up my installation to react to the lighting levels in the room, added the ability to control the volume of my installation remotely via a bluetooth phone, fine-adjusted the timings of the sliders, made a script to start up the necessary software when the computer was started up, and close them in order when the computer was shut down and finally scheduled the computer to automatically start in the morning and shut down in the night. Not everything went perfectly in my first installation: I had problems with the light sensors (which I disabled after a day or two) and mainly with the projection size: I had provided the instructions of my installation to the organising team, and trusted that all was well, but the projector was not capable to produce a big enough image. I visited the exhibition place many times each day I was in St. Etienne, and checked out for any possible problems, and made solutions for how to solve them. All of this taught me a valuable lesson: one has to know the details of the software, the operating system, the computer, the audio and video projection system, the physical installation and the spatial situation. Presenting interactive installations is a context-sensitive and multi-sensory task, and these should be taken in account during the creative process, since they affect the way that the work is interacted with (Beyer & Holtzblatt, 1998.)

Early on in the research process, the doctoral dissertation was positioned as an artist-centred inquiry to the creative process of making interactive art. I spent quite a lot of time defining and analysing some key concepts in the field, such as interactivity and user interface. I positioned interactive art as a smaller subfield of media art, which in this research is sort of a mothership, containing other genres such as sound art, video art and even the ever-changing and unstable field of new media art. While new media art and interactive media art seek new platforms, genres, topics, technologies

Picture 2. Climatable

and types of engagement, they already have a history, a multitude of artworks with which new artworks can create a dialogue with. The interactive work Climatable (Picture 2) clearly is one embodiment of a “typical” media art work: a table with an image projected from above, which is interacted with simple actuators (linear sliders). Using a form which perhaps is familiar already from other contexts — not only from interactive art exhibitions but also from fairs, science centre exhibitions and even places like airports and shopping malls — can be also a way to achieve simplicity.

I do acknowledge that creating categories, dichotomies and binary positions can lead to narrowminded thinking. I have taken this dangerous path: interactive art and interaction design are discussed as two different, separate disciplines. It is impossible to say how many percent of interactive art contains interaction design, or that creating interactive art is a skill every interaction designer should have. However, in my dissertation this division — and on the other hand the overlapping of the two — is present. This has been done to take in consideration how we culturally discuss and perceive these categories. The context in which we situate an interactive artefact affects how we perceive it: when talked about as an art object, we map certain aspects to it which differ from the features which would be present if the artefact is seen as a design object. For example, design objects typically are perceived as utilitarian: they have a practical function, and are handled, manipulated and controlled whereas one is not even allowed to touch a typical art object. Art objects can introduce new ideas, fire up the imagination, allow for multiple and even contradictory interpretations, guide the audience to new experiences. These two worlds come together even in the title of the research: I have chosen to talk about designing art. Methods and practices which we relate to making art as well as methods and practices which we relate to design are both present in the research when my interactive installation Climatable is discussed.

Even before the initial display of my work Climatable I had decided to concentrate on improving the usability of interactive artworks. To fight unnecessary confusion, the concept of simplicity seemed to be a fruitful and fresh approach. After some research on the concept, it was noticed, that even though keeping things simple is regarded as one of the golden rules of design, no-one had really explained what it means clearly.

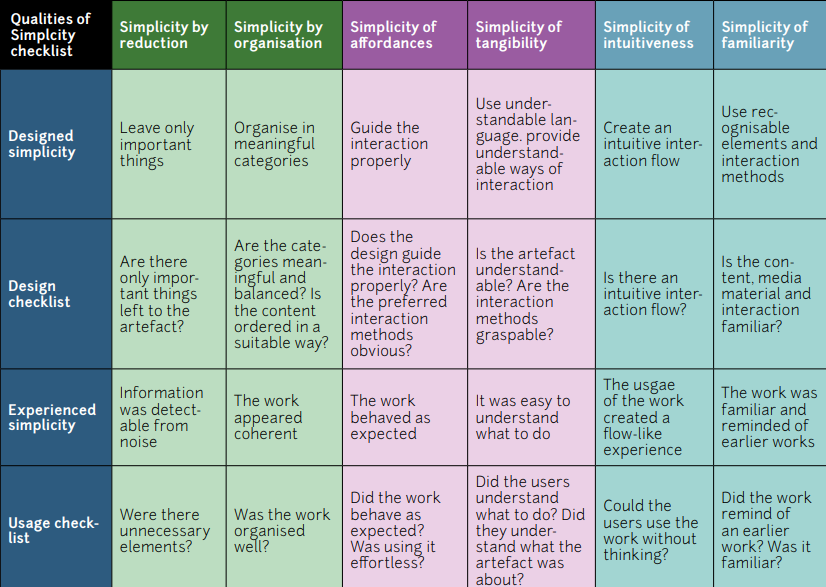

Picture 3. Qualities of Simplicity

John Maeda gave it a go in his book The Laws of Simplicity (2006), and his 10 laws are great, but there is no consistency between them. However, his work was really influential for my research. So, by analysing my own and other artists interactive artworks, talking with users and observing them, and by doing a design research review, I decided to define Simplicity in my own terms, as a set of qualities.

The Qualities of Simplicity as defined in this research are: reduction, organisation, affordances, tangibility, intuitiveness and familiarity. Together they build up trust towards the interactive artefact. The qualities can be further grouped as formal, functional and conceptual qualities (Picture 3).

Working with the Qualities of Simplicity from a designerly perspective allowed me to combine the qualities to the idea of interactive art as a multi-sensorial and contextual entity. By conducting user observations made in St. Etienne and rethinking my work from a personal, heuristic point of view, I was able to collect information to a Simplicity Matrix. Looking at the interactive installation Climatable from various points of view different expressions of simplicity were found. Also research review was done, an email survey with young interactive artist was conducted, other artists’ interactive works were analysed along with my earlier works. The matrix building provess was an iterative process during which the Qualities of Simplicity were refined, examined and even discovered and abandoned.

Table 1. The Simplicity Matrix of Climatable.

After a while I realised that the findings I had collected were different in nature. The Qualities of Simplicity were related either to my design decisions or to expressions, which were observed by the users, sometimes even both. This led to a fundamental change in the matrix, and reminded also me that in designing interactive artefacts, the artist should always have knowledge about the user. The designer has of course knowledge of her own craft, but should also collect as much knowledge as possible of the users: what they expect, how they behave, what they do, how did they feel etc. While these aspects were not ignored, they were mixed up in the research along with my design desicions. I had to step away from being the bloody artist myself! The matrix was reformatted to display both designed and experienced Qualities of Simplicity (Table 1). This dual thinking of Simplicity even affected my research main questions. It could be said that at this point my study tilted from a art-led research process in which the artist’s own viewpoint is of central importance towards a design research process, in which the knowledge is constructed in cyclical iterations involving presenting the interactive artefact in public, making refinements to it and analysing the results also from the observed usage point of view as well (Koskinen et al, 2011).

Table 2. The Simplicity Framework.

In the research Qualities of Simplicity in designing interactive art also a designers tools or checklist is presented, which I call the Simplicity Framework. It can be regarded as a generalised model of the Simplicity Matrix (Table 2). The Matrix and the Framework were born side by side during the iterative design -research process, both influencing each other: the practical notions made up for the matrix were generalised in the Framework, which in its turn helped to fill in potential gaps in the Matrix. The Simplicity Framework can be useful as a check-list when designing interactive artefacts before or during the design process — essentially a new Simplicity Matrix can then be populated with the findings. It is noteworthy to say, that true data from experienced simplicity can only be gained by designerly methods: observing, interviewing, conducting surveys etc. This can be seen in the Framework: the design checklist questions are in the present tense, while the experienced usage checklist questions are in the past tense.

While simplicity as a method for achieving usability was emphasised in the early stages of the research, the role of usability diminished as the research matured. Simplicity was seen as a quality not only related to usability, but also as something which can raise curiosity, guiding the interaction towards more complex interactions as the artefact or its context changes. The interactive artefact changes the role of the art visitor — in interactive art major role in the aesthetic art experience is the physical participation with the work (Huhtamo, 2007). Interactive installation situations typically allow for many people to observe and even interact simultaneously, and this creates various different types of roles for the audience: from an observer to the manipulator of the work, even all the way to become a performer of the work for others (Dalsgaard & Hansen, 2008). Simplicity allows not only for initial access of the work, but also helps keep up a fascinating and easily followable interaction flow, which allows for continued exploration of the work. This exploration allows for understanding the artefact’s contents, rules, limitations and possibilities. When these are understood by the participant, in social situations an even more active role is possible. Performing the work to the other people creates a situation, in which the audience member actually and physically communicates his / her findings to others, shows features which are interesting for him / her, plays around with the work etc. As showcased here, creating socially playful interactions is a complex process. Simpicity should be present to allow initial access for the artefact, to allow the interaction exploration happen and the content and the interaction possibilities to be understood, all the way to allowing performing the work to others. Perhaps it can be argued, that creating for this kind of playfulness, social exploration and performativity is not a mandatory requirement from all interactive artworks or installations. However, these types of interactive artefacts have been present in interactive art for quite some time, and they are also heavily present in current day interaction design research. My research also implicitly argues, that many artists have mixed creating complex art to creating confusing interactions and interfaces. In my opinion they have not understood that it is possible to create complexity through simplicity, complexity built step by step, using simpler building blocks or puzzle pieces. It is a creative skill to get people to interact, not to create impossible interfaces. Novel interfaces can and should be explored by artists and designers, but too much confusion guides the people away. It should be remembered, that the users create the work, and a fluid interaction is what helps to create this authorship. Perhaps the quote from the beginning should be changed in to:

“I'm the bloody user of the work, it has been made in a confusing way, if the artist doesn’t understand it then forget about it!”

References:

Beyer, H., & Holtzblatt, K. (1998). Contextual design: Defining custom-centered systems. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann.

Dalsgaard, P., & Hansen, L. K. (2008). Performing perception — staging aesthetics of interaction. Transactions on Computer- Human Interaction (tochi), 15(3), 13. https://doi.org/10.1145/1453152.1453156

Huhtamo, E. (2007). Trouble at the Interface 2.0. On the Identity Crisis of Interactive Art. Retrieved from http://www.neme.org/591/trouble-at-the-interface-2. Accessed June 5, 2018.

Knuutila, T. (2000). Collagerator. [CD-ROM].

Knuutila, T. (2008). Climatable. [interactive installation].

Koskinen, I., Zimmerman, J., Binder, T., Redtröm, J., Wensveen, S. (2011). Design Research through Practice: From the Lab, Field, and Showroom. Morgan Kaufmann

Maeda, J. (2006). The Laws of Simplicity. MIT Press.